Nearly a decade ago, Congress tasked the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the U.S. Department of Education with developing a National Reading Panel that would evaluate all existing research to find the best practices in teaching children how to read.

This landmark study was released in April of 2000 and highlighted for educators and parents what has become known as “the big 5” in reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, comprehension and fluency.

To read the original study: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/nrp/Pages/smallbook.aspx

The National Reading Panel describes phonemes as, “the smallest units constituting spoken language.” In all, English has anywhere from 41 to 44 phonemes (the number depends on which classification system is used). Phonemes combine to form syllables and words. The Panel included phonemic awareness because many studies over the years have identified it and letter knowledge as the best predictors of how well children will learn to read during their first two years in school.

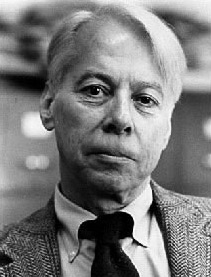

“…learning to read is hard for nearly all children and extremely hard for some.”

—Alvin Liberman, speech perception pioneer

It’s worth noting that phonemic awareness is not to be confused with ‘phonological awareness.’ Phonological awareness is an umbrella term that includes phonemic awareness, as well as a number of other abilities including being able to distinguish rhyming words and to divide sentences into words.

As Dr. Louisa Moats and Susan Hall explain in their 2002 book, Parenting a Struggling Reader, “Phonemic awareness is not the only skill you need [to learn how to read], but you must have it in order to develop decoding and word recognition skills. It’s like needing to know the finger positions for all the notes on a musical instrument before you learn to read music and play new pieces.”

Typically, people with dyslexia have weak phonemic awareness, meaning they have difficulty hearing the fine distinctions among individual sounds. And they aren’t the only ones: it’s estimated that without direct instructional support nearly 25 percent of middle-class first graders also struggle with this skill.

But how did researchers and educators come to understand the importance of phonemic awareness?

You have to go back to the mid-1950s and the Haskins Laboratory, founded by Caryl Haskins, a scientist who created pioneering work in the study of ant biology. (More on Haskins, here: http://www.haskins.yale.edu/history/haskinsbio.pdf) Based in New York City and later at Yale University, the Haskins Lab was home to researchers working across disciplines on a variety of issues, including the needs of World War II veterans.

Among their projects was the development of prosthetic devices for the blind. The team at Haskins included a young researcher, Alvin Lieberman. Trained as a psychologist, Liberman had devoted much of his time to studying the growing field of speech perception. As part of the Haskins’ Lab work, Liberman and his team set about creating a reading machine for the blind that could scan and read back texts automatically.

According to Dr. Marilyn Jager Adams, author of the 1997 book, “Phonemic Awareness in Young Children,” (Available from IMSE, here: https://www.orton-

Liberman and his team came to understand that, “…phonemes are not [distinct] audible signals. Using their equipment they showed how phon emes are blended together and co-articulated in spoken language.”

emes are blended together and co-articulated in spoken language.”

In his landmark 1967 paper, “Perception of the Speech Code,” Liberman outlines how a word like ‘cats,’ when spoken appears to be one sound, but is a group of distinct sounds blended together. Add in differences in the ways in which words are pronounced—the /s/ in ‘cats’ can sound, instead like a /z/, but the listener, in decoding what’s being said, understands that ‘cats’ are ‘cats,’ despite those variances in pronunciation—and it becomes easy to see how learners can get tripped up trying to understand how words are constructed when every sound is not distinctly pronounced.

To read Liberman’s paper: http://www.haskins.yale.edu/Reprints/HL0069.pdf

As the forward of Dr. Adams’ 1997 book puts it, “Before children can make any sense of the alphabetic principle, they must understand that those sounds that are paired with the letters are one and the same as the sounds of speech. …research shows that the very notion that spoken language is made up of sequences of these little sounds does not come naturally or easily to human beings.”

Liberman went on to develop the motor theory of speech perception and headed the Haskins Lab at Yale from 1975 to 1986. His work remains highly cited and influential today.

Indeed, educators in the classroom benefited from years of research based on and inspired by Liberman and his team’s findings. By the late 1990s, the National Reading Panel (NRP) found more than 1,900 citations in reading studies devoted to phonemic awareness. Upon further review, 52 studies fit the NRP methodology criteria and the results were clear: children who received direct instruction in phonemic awareness showed improvement in reading and spelling.

“Phonemic awareness is not the only skill you need [to learn how to read], but you must have it in order to develop decoding and word recognition skills.”

—Dr. Louisa Moats and Susan Hall

Today, states like Virginia, Wisconsin, Iowa and Delaware all provide phonemic awareness testing for early readers to help more quickly assess and ultimately remediate children who struggle to recognize phonemes.

In Wisconsin, for instance, teachers use the Phonological Awareness Literacy Screening system (PALS) to assess and monitor students’ progress from Pre-K through second grade. Schools are required to provide parents and legal guardians with each student’s results and to provide remedial reading instruction if a student is struggling.

To learn more about Wisconsin’s PALS program: http://dpi.wi.gov/assessment/pals

PALS provides teachers and parents with testing benchmarks for students at three levels:

- In Pre-K, students are expected to be able to write their names and have knowledge of the alphabet

- In Kindergarten, students need to be able to recognize words in isolation and understand letter sounds

- By second grade, students are tested on their oral reading abilities and spelling

For more information about phonemic awareness research, benchmarks by age, as well as tips and activities, head over to Reading Rockets: http://www.readingrockets.org/teaching/reading101/phonemic